# Addition: Add 2 and 100,000

2 + 100000

## [1] 100002

# Subtraction: Subtract 5 from 3

3 - 5

## [1] -2

# Multiplication: Multiply 71 by 9

71 * 9

## [1] 639

# Division with Order of Operations

90 / ((3 * 5) + 4)

## [1] 4.736842

# Power: 2 to the power of 3

2 ^ 3

## [1] 8Arithmetic Operators

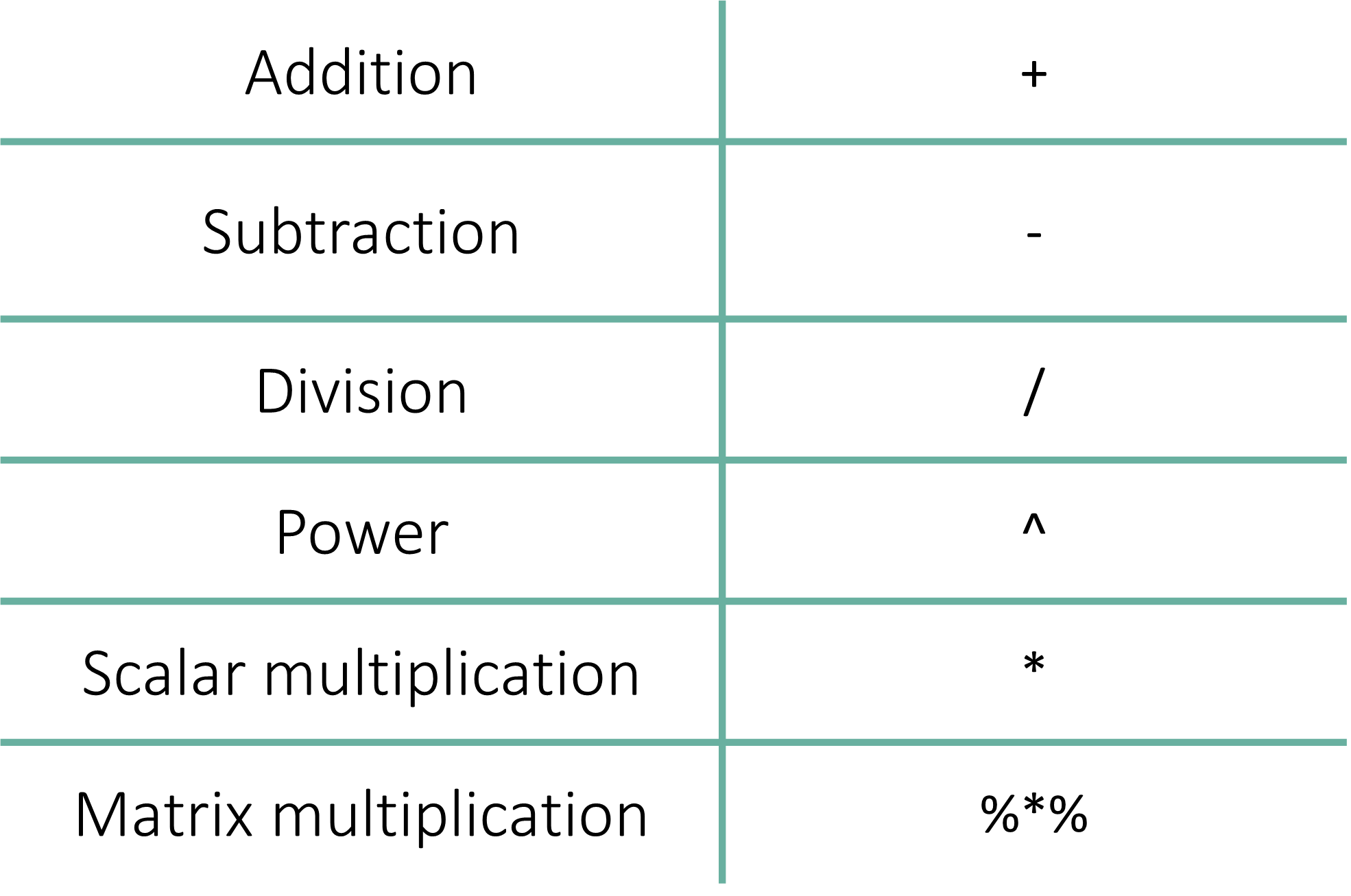

An operator is a symbol or keyword that tells the computer what operation it should perform on values or variables. The arithmetic operators perform mathematical calculations.

At its most basic level, R is a powerful scientific calculator. It handles standard arithmetic as well as complex matrix operations required for bioinformatics.

The fundamental operations include addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Beyond these, R handles powers (exponents), modulus (remainder from division), integer division, scalar multiplication, and matrix algebra.

1. Basic Arithmetic

Standard operations follow the symbols you are likely already familiar with:

| Operation | Operator | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Addition | + |

2 + 100000 |

| Subtraction | - |

3 - 5 |

| Multiplication | * |

71 * 9 |

| Division | / |

90 / 19 |

| Power | ^ |

2 ^ 3 |

Examples in Action

A Note on Coding Style: To Space or Not to Space?

In R, spaces around operators are generally ignored by the computer, but they matter a lot for human readability.

- Standard Style (Recommended): Use a space before and after the symbol:

1 + 1. This is the professional standard (often called the Tidyverse Style Guide). It makes your code much easier to read. - Compact Style: No spaces:

1+1. This works perfectly, but can look “cramped” in long equations. - Inconsistent Style (Avoid): Using space on only one side, like

1+ 1or1 +1.

Professional Tip

While R will run your code regardless of the spacing, consistency is key. Keeping a clean, spaced-out style helps you (and your PI) catch errors more easily when reviewing your analysis later.

2. What can be used with Arithmetic Operations?

In research, you won’t just be typing raw numbers. You will frequently perform calculations using objects (variables) that store your data. You can mix and match numbers and objects freely.

Example: Number with Object

num <- 2

1 + num[1] 3Example: Object with Object

num1 <- 2

num2 <- 3

num1 * num2[1] 6Wait, what is <- ?

In the code above, we used the <- symbol. This is an Assignment Operator. It is used to store data into the object it points to. Think of it as an arrow putting a value into a labeled box.

We will explore this in depth in the next chapter, but for now, just know that num1 <- 2 means the box labeled num1 now contains the number 2.

3. Operator Precedence

Not all operators are created equal.

R follows a specific order of operations (similar to high school mathematics, often called PEMDAS). For example, multiplication (*) and division (/) will always be performed before addition (+) and subtraction (-).

results1 <- 1 + 2 * 3

results2 <- (1 + 2) * 3

results1

## [1] 7

results2

## [1] 9Best Practice: When in doubt, use parentheses (). They have the highest precedence and ensure R calculates your formula exactly how you intended.

4. Vectorized Operators

Unlike many other programming languages, R is designed specifically for statistics. This means its operators are vectorized.

If you have a list (vector) of 1,000 patient ages and you want to add 10 to all of them, you don’t need to write a complex loop. R simply applies the operation to every single value in the list simultaneously.

# Example: Adding 10 to a vector of three ages

ages <- c(20, 30, 40)

ages + 10[1] 30 40 50In most programming languages (like C++ or Java), if you want to perform math on a list of numbers, you have to write a “For-Loop.” This tells the computer: “Look at the first number, add 10, save it. Now move to the second number, add 10, save it…”

To add 10 to each without vectorization, you have to create a container and manually iterate through every position, be like:

ages <- c(25, 30, 45)

new_ages <- c() # Create an empty container

# The Loop: Adding 10 one-by-one

for (i in 1:length(ages)) {

new_ages[i] <- ages[i] + 10

}

print(new_ages)[1] 35 40 55